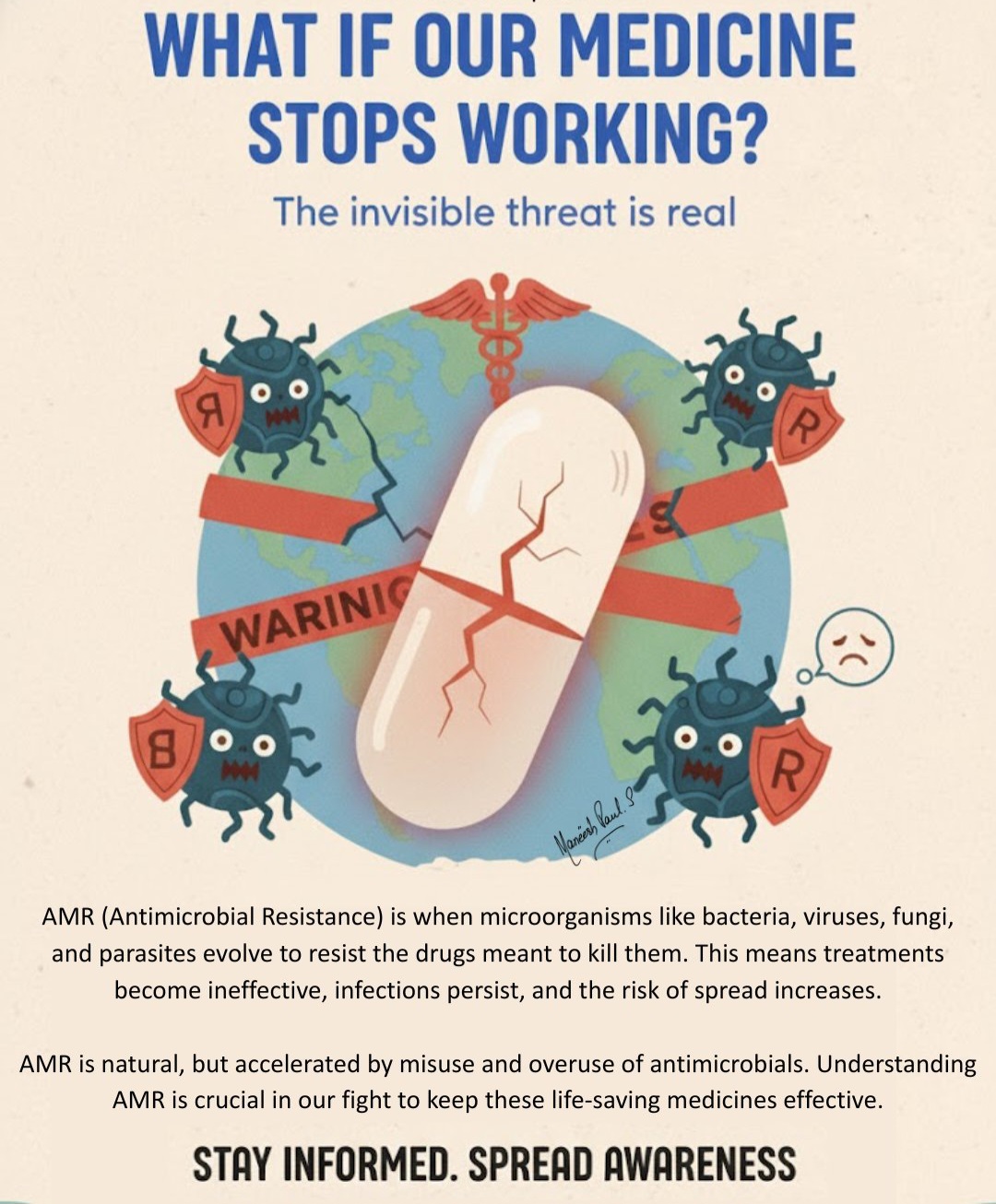

1. What is AMR in simple terms?

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) happens when germs (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites) change over time and no longer respond to the medicines designed to kill them, such as antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, and antiparasitics.

That means:

- Infections become harder to treat

- Medicines that used to work may fail

- The risk of severe illness, disability, and death increases

Global data in 2019 state that, bacterial AMR alone directly caused over 1.2 million deaths and was also associated with nearly 5 million deaths.

2. Why is AMR a big deal?

AMR is now one of the top global public health threats.

If we don’t act:

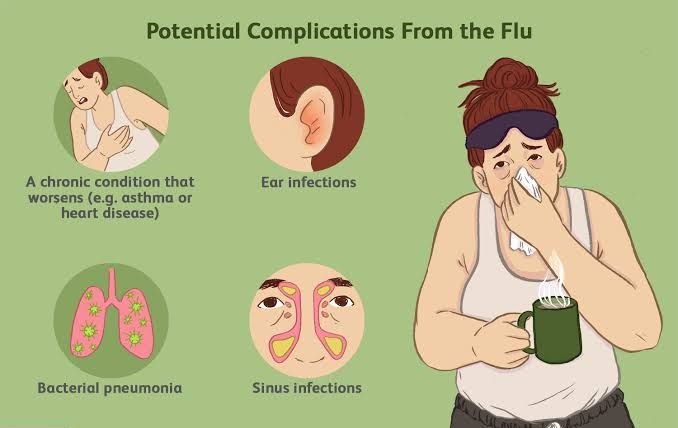

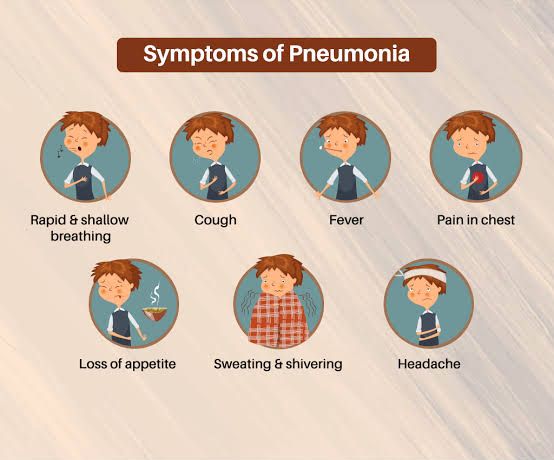

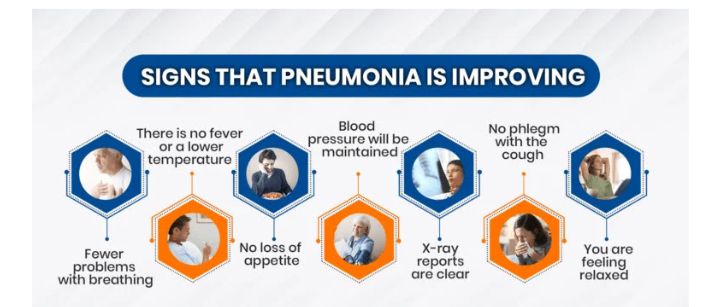

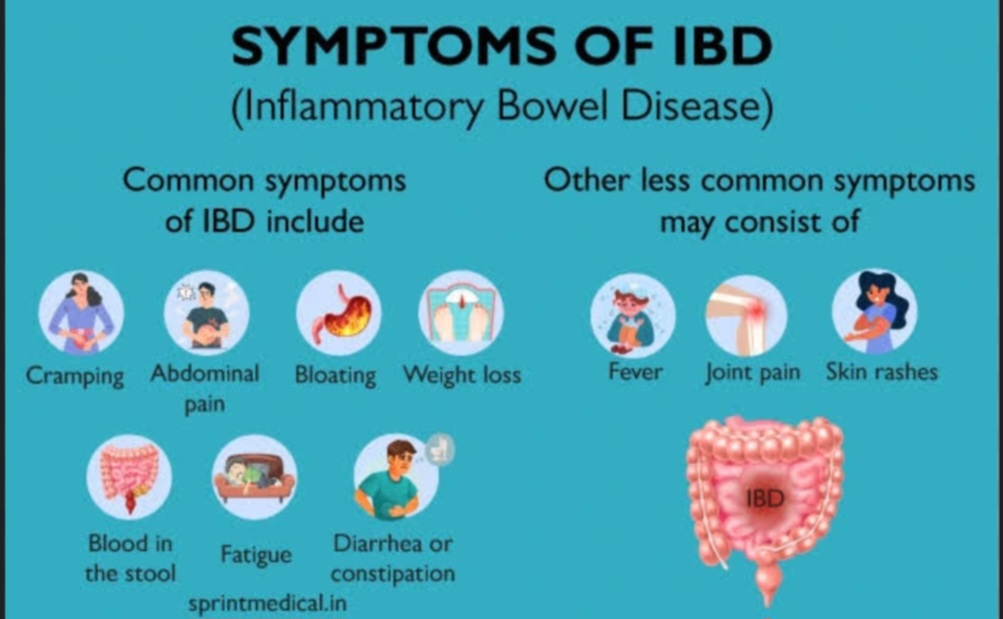

- Common treatable infections like UTIs, wound infections, and pneumonia could become life-threatening.

- Common procedures (C-sections, cancer chemotherapy, joint replacements, dialysis) may become too risky.

By 2050, millions more deaths may occur every year due to drug-resistant infections. Recent WHO data show that around 1 in 6 bacterial infections is already resistant to standard antibiotics, with especially high resistance levels in many low- and middle-income countries.

3. What causes AMR?

The main drivers are misuse and overuse of antimicrobials in humans, animals, and agriculture.

Key examples:

- Taking antibiotics when they’re not needed

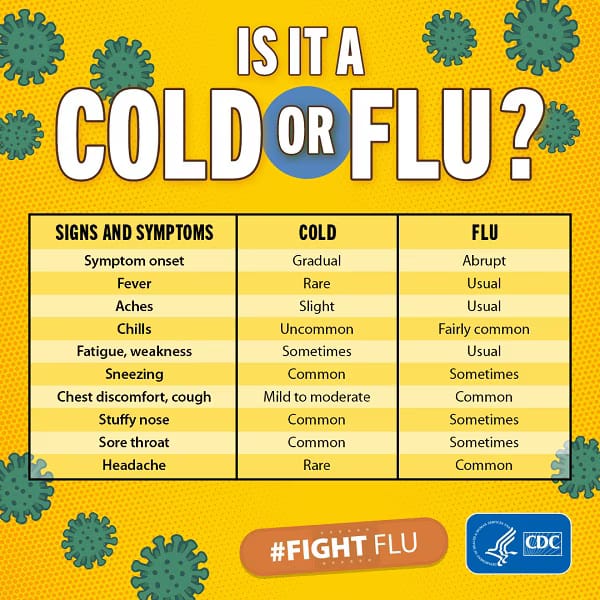

- Using antibiotics for viral infections like flu, colds, most sore throats, or COVID-19

- Self-medicating or buying antibiotics without proper prescription

- Not using antibiotics correctly-Wrong dose, wrong duration, wrong frequency, Stopping the medicine when you “feel better” instead of finishing the prescribed course

- Overuse in animals and farming

- Antimicrobial use in crops and aquaculture, which can drive resistance in the environment

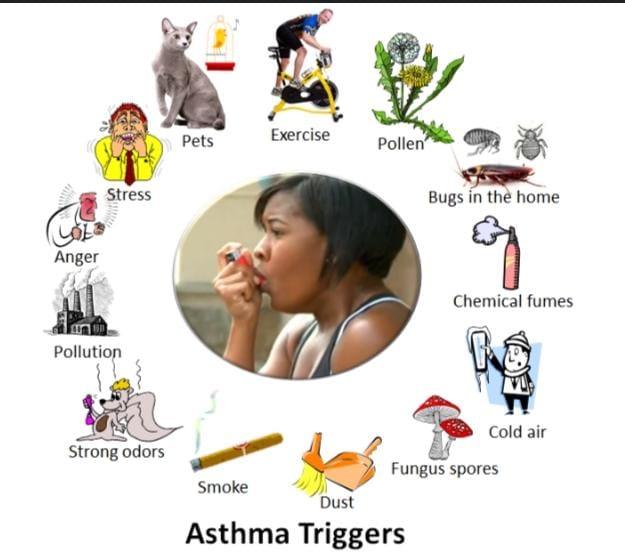

- Poor infection prevention and control-Inadequate hand hygiene, sanitation, and vaccination coverage

- Overcrowded hospitals and lack of proper cleaning increase spread of resistant germs

- Environmental pollution- Drug residues from pharmaceutical factories, hospitals, farms, and sewage enter water, soil, and ecosystems, giving bacteria constant low-dose exposure and encouraging resistance.

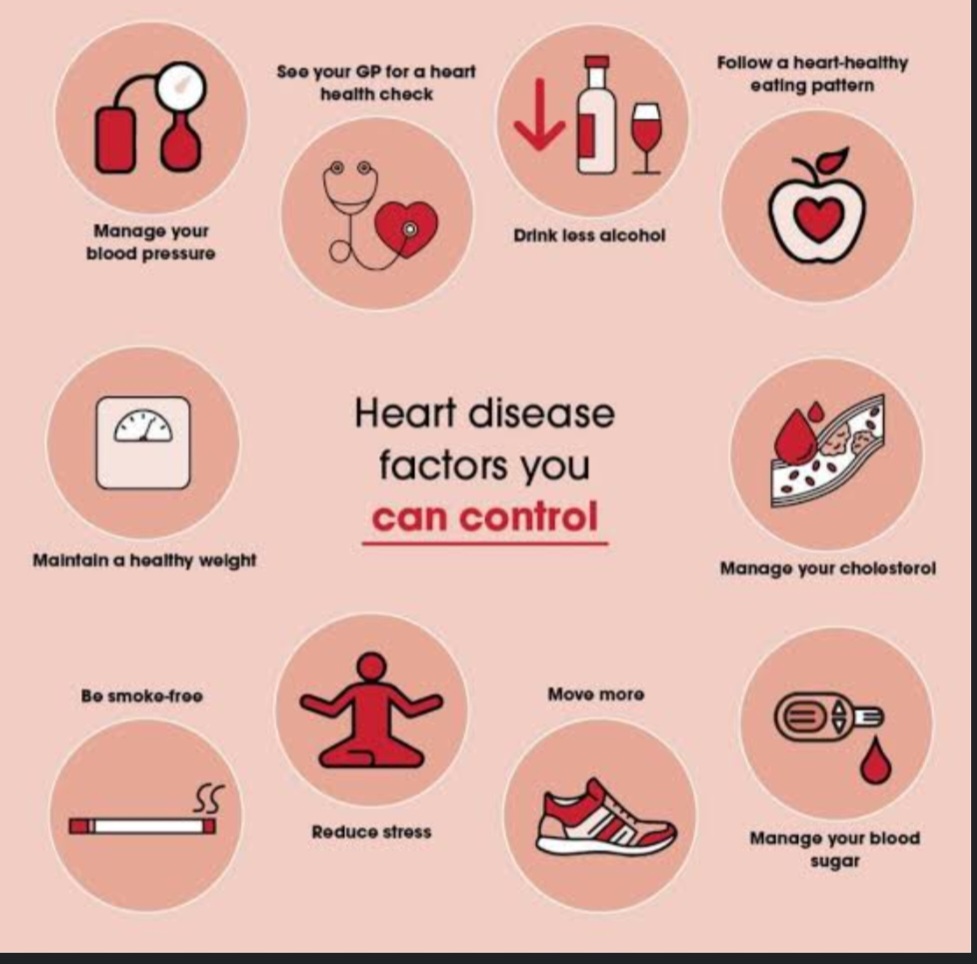

5. Practical health tips

How you can help stop AMR:

A. Use antibiotics wisely-Never demand antibiotics for colds, flu, or other viral illnesses. Trust your healthcare provider’s judgment.

-Only take antibiotics prescribed to you by a qualified healthcare professional.

-Do not share or use leftover antibiotics.

-Follow the prescription exactly: right dose, at the right time, for the full duration – even if you feel better.

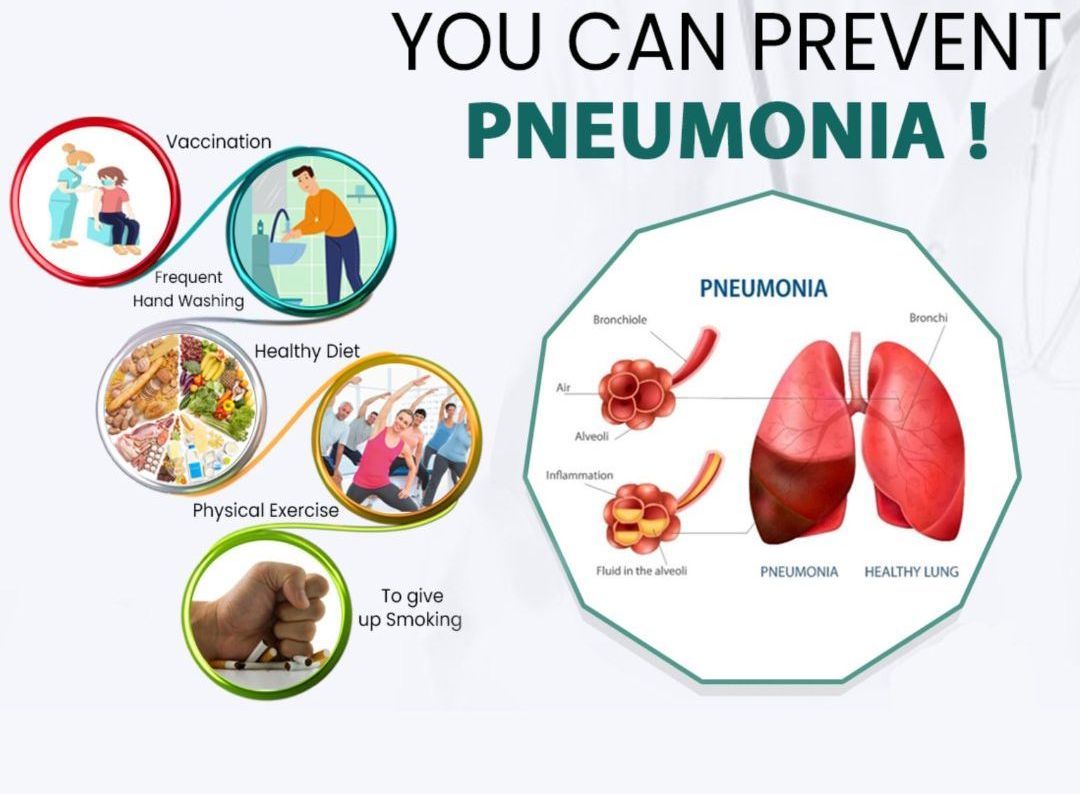

B. Prevent infections in the first place

-Every infection you avoid is one less chance for resistance to develop.

-Wash your hands regularly with soap and water (especially before eating, after using the toilet, and after touching animals or raw meat).

-Keep vaccinations up to date (for yourself and your children). Vaccines reduce the number of infections needing treatment – and so reduce antibiotic use.

-Practice safe sex (condoms, regular STI screening).

-Prepare food safely – wash hands, cook meat thoroughly, avoid cross-contamination between raw and cooked foods.

-Protect and clean wounds quickly to prevent infection.

C. Protect others

Stay home when you’re very sick to avoid spreading germs.

Cover coughs and sneezes with a tissue or your elbow.

If you’re given infection prevention instructions in hospital (like hand rub or protective clothing), follow them strictly.

D. Support a clean environment

Dispose of unused or expired medicines safely – don’t flush them into toilets or the environment; return them to pharmacies if such programmes exist.

Support policies that improve wastewater treatment, reduce pharmaceutical and agricultural pollution, and protect water and soil from contamination.

E. If you are a health worker or student

Prescribe antibiotics only when they are clearly needed, using clinical guidelines and local resistance patterns.

Take samples (e.g., cultures) when appropriate to guide therapy.

Use the narrowest effective antibiotic for the shortest appropriate duration.

Practice and enforce strict infection prevention and control – hand hygiene, cleaning, isolation when needed, and antimicrobial stewardship activities.

Educate patients in simple language about why antibiotics are not always needed and what they can do instead.

N/B: “Not every infection needs antibiotics. Ask: ‘Do I really need this antibiotic?’” “Educate. Advocate. Act now: together we can slow antimicrobial resistance